Archives

- 2011/09/22Day 32 of shooting

- 2011/09/21Day 31 of shooting

- 2011/09/20Day 30 of shooting

- 2011/09/08Day 29 of shooting

- 2011/09/07Day 28 of shooting

- 2011/09/06Day 27 of shooting

- 2011/09/05Day 26 of shooting

- 2011/09/04Day 25 of shooting

- 2011/09/03Day 24 of shooting

- 2011/09/02Day 23 of shooting

- 2011/09/01Day 22 of shooting

- 2011/08/30Day 21 of shooting

- 2011/08/29Day 20 of shooting

- 2011/08/28Day 19 of shooting

- 2011/08/27Day 18 of shooting

- 2011/08/26Day 17 of shooting

- 2011/08/25Break in the shooting

- 2011/08/24Day 16 of shooting

- 2011/08/23Day 15 of shooting

- 2011/08/22Day 14 of shooting

- 2011/08/21Day 13 of shooting

- 2011/08/20Day 12 of shooting

- 2011/08/19Day 11 of shooting

- 2011/08/18Day 10 of shooting

- 2011/08/17Day 9 of shooting

- 2011/08/16Day 8 of shooting

- 2011/08/15Day 7 of shooting

- 2011/08/14Break in the shooting

- 2011/08/13Day 6 of shooting

- 2011/08/12Day 5 of shooting

- 2011/08/11Day 4 of shooting

- 2011/08/10Day 3 of shooting

- 2011/08/09Day 2 of shooting

- 2011/08/08The 1st day of shooting

- 2011/08/04All staff meeting

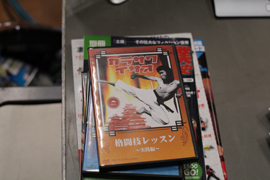

Looks like a martial arts instructional video by Action director Karasawa-san has just gone on sale. (I’m only kidding. It’s actually a prop for the story.)

Discussing final details on set with Art director Nori Fukuda. It truly is the planning and execution of a giant play.

Today is a break in the shooting so it should be a day off, but there’s no rest for the main production staff. We met in front of the Subaru Building and then drove nearly 2 hours to do preliminary checks on a location set. All the preparations for this film, from screenplay to storyboard, production, and shooting have been left to Nishimura Eizo and yet when I arrive at the last minute and start giving my opinions and adjustments on everything from A to Z, they follow my lead 100%. I am truly grateful and even if it is a little presumptuous of me to say so, I respect the way they work. I didn’t think Nishimura-san would actually be this devoted and committed. This was especially true of the script, where they remained incredibly flexible and were able to fully integrate some of the more radical ideas I had. I was quite moved. I don’t think this is simply a function of his long career in shooting advertisements. With that said, however, he has a number of works to his name and yet is never arrogant, always kind, and creates a set that places creativity above all else. This is completely different from the standard method so common to postwar Japan of inflating a tiny ego to grotesque proportions and using that to manage. In Nishimura, I see the attitude of a true pro.

I too have done collaborations with a lot of brands in other fields. My philosophy on collaborations has always been to try to reflect 100% the aims of my collaborator and to make sure they are fully satisfied with the result. I’ve concentrated on valuing my partners’ aims more than my own. And that is why when I collaborate with someone, they come back again and again. That is the evidence that they are satisfied.

I’m not someone who is capable of creating on my own. I do not have that kind of talent. However, I have spent the last 20 years perfecting the skill of pushing the talent of those around me to its outermost limits, occasionally even creating conflict in order to push them to over 100% of their potential and integrate that in to the work. This has led me to be mocked and misunderstood by many. However, I also believe that there is no other field which allows you to apply and test the limits of your abilities and experiences as much as collaboration.

Perhaps the area where I have made the most discoveries on this film is set decoration. Even I’ve been surprised at how much I’ve responded to this area, sometimes even delaying shooting to go over the fine details, much to the chagrin of the crew I’m sure. Perhaps it’s because this area is closest to my own territory as a contemporary artist. Just like with installation of artworks, I begin seeing noise in the corners of my vision. If I have another chance to do a live action film like this, I’d like to put even more energy and attention in the sets.

With that said, everyday on this project is one of creativity and enjoyment.

The 6th Day of Shooting

Staff gather every morning at 6 in the Subaru building, ride to the location in a bus and work with out rest for the remainder of the day. I often wonder if they have time to sleep, but they still manage to change clothes everyday and deal with all the regulatory hurdles on set. I’ve tried to divulge their secrets from crew-chief Shio, including how he makes his selections, but all he’ll tell me is the obvious – “the ones who can handle it are the ones who survive.” All of them are freelance and work on a project-by-project basis, so if they don’t prove useful, they have no future. I don’t know if it’s because movies have established a place for themselves in society but… the grass is looking greener on the other side of the fence.

Looking back, I realize that we in the art world pay witness every year to 10,000 new creative zombies who emerge from art schools across Japan. Each of them has been imprinted with meaningless dreams by the crap education system and they are thus unable to connect with the world at large. It’s all about “me me me”.

They come in, go all through all sorts of things in their first three months, unable to perform any tasks smoothly, and then announce “I’ve had enough,” before making their blank faced resignations.

When oh when will the art world become a place capable of evolving, a treasure trove of excellence. I’d like to try building that sort of environment by hiring part-timers in their first years of college and educating them. This feeling has become stronger after seeing the deep level of skill present on the Jellyfish Eyes set and provided by Nishimura Eizo.

Stylist Kazuki Yunoki.

I met her when I was creating my artwork Inochi. Afterward, she served as a stylist on Mr’s short film Nobody Dies and a collection of photographic works I did. She created the impetus that got this project rolling.

Photo and video archivist Akihide MishimaHe came all the way from Osaka. In the past, he’s helped make promotional videos for GEISAI and other projects.

The Japanese superhero Ultraman and the Ultra Seven were created by the company Tsuburaya Productions. That company was itself founded by Eiji Tsuburaya. Godzilla, Radon, Mothra, and lastly, the Ultra Series itself – this company produced an incredible amount of works which imbued the genre with enough realism to capture the imaginations of the children of my generation. During the company’s heyday, Japan was the major superpower in the special effects world but since Starwars, that mantle has been taken by Hollywood.

Stories weave together the light and shadow of our times. In Eiji Tsuburaya’s time, Japan was still awash in the anxiety of the post-war period. These anxieties then took the form of yokai and were used to express adults’ concerns to their children. Shigeru Mizuki’s Ge Ge Ge Kitarou also used this same mix of social commentary, narrative, and yokai. Soon after, Japan entered into the age of the bubble economy and began heeding the rallying cry of economic globalism: “economics is the one true faith.” The idea of monsters and yokai as a metaphor for shapeless anxieties lost its impact. Instead, these monsters and other characters began to populate video games, where they became the allies and friends of children, filling in the communication void that existed between children and their parents. Now, however, in the aftermath of the disasters of a few months ago, Japan is once again enveloped in worry and unease.

What is a nation? Who bears responsibility for the mistrust we feel toward our politics? Why can’t we stop the advance of nuclear power? The powerlessness I felt in my childhood when faced with the structure of the cold war and the fighting in Vietnam, the sense of urgency that it wrought, have returned these past months. We are no longer in need of “monsters” living next door who serve as symbols of our loneliness. We have once again entered into an age that needs yokai and fearsome beasts. Jellyfish Eyes is thus a work with post-disaster Japan as its theme.

We aim to present a passionate message, free of duplicity, to the children of today. In the center of this photo is production member Yuji Sato.

Thanks for everything from location scouting to organizing the overall team.

Extras on the move

This is how we will continue pushing the shoot forward.

Yuta Okuyama from Special effects. Yuta has been busy creating an array of creatures. On the right is assistant producer Nanae Yoshida from Nishimura Eizo.